“Yugoslavia: From the beginning to the end” at Muzej istorije Jugoslavije

We can get the good stuff out of the way first. No, too cynical, what’s good is good in fact. It’s the first exhibit, that I know of anyway, that was organised cooperatively by historians from erm, a majority of the former Yugoslav states. And it does some decent things, including things that are usually excluded and ought to be in there (like the state that existed from 1919 to 1941 and the movement to create it), and excluding some things that made a claim to be there which ought to be ignored (like the “state” that was founded in 1992 and like the film character Jason died more than once, in 2003 and 2006).

There are a few other things that are meant to look good but it is hard to be sure. Like the introductory mini-essay by the curators where they try to step away from claims to the authoritative character of their own work and say simply that they are telling “just one of the many stories about Yugoslavia.” This is kind of truish, but then it is also the case that not every story is told across hundreds of square metres of floor space in the only museum that is functioning in what used to be the capital city of a country that mattered. Engaging institutional might and claiming it means nothing at the same time tells us some things about responsibility that people who make use of it would rather we do not know, first among those is that once you have taken advantage of it, the right to relativise it no longer belongs to you but to other people.

About the exhibit itself, the first thing visitors will notice is that it mostly nods to the visual. Most of what it presents is text, beginning with a “chronology of Yugoslavia” along a big wall where visitors enter. If I had read through that enormous mass of tiny print I am sure I would have been the first person to do it. The pattern is repeated elsewhere, and one gets the impression that one is seeing a not quite completed exhibit accompanied by constant explanation of what the authors would have intended to have done under different circumstances.

So what was Yugoslavia? We get a couple of ideas directly in the room dedicated to the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. First of all, it was a union of Serbs, Croats and (sort of) Slovenes. There were some other groups of people, but they mostly get a mention at the bottom of blocks of text. “Non-Slavic” peoples, does such a thing really exist? Second, it was (says a lovely beige text board) “a desperate cry of the oppressed in the big empires” while simultaneously being (according to another beige mass) “the dream of the … elite.” An oppressed elite is pretty much good for nothing, so they fouled up the job and in steps the law firm of Koštunica and Čavoški to tell us the result: the NDH “committed genocide” while the Chetniks “committed genocide-like massacres.” This was apparently the only thing that happened during the period of the Second World War, except for a few incidents that got moved into another period, about which more in a bit.

About those ethnicities that kept killing each other or engaging in killing-like massacres: what was their deal? We’re lucky to have historians here! Because they are able to explain to us that empires indelibly stamped the personalities of people who had no experience of them in ways that no oppressed elites, however impressive their uniforms, were capable of correcting. But let’s get it from the beige wall.

But wait, you say, you don’t know any Ottomans or Austro-Hungarians nurturing hatred for one another as they polish their handžars and Sachertorten, but you do know a bunch of people who were pretty well satisfied with Yugoslavia and even happy to identify with it. Don’t say that you do not trust historians to give you an answer, the fact that they know about path dependency does not mean that they do not know about laziness. Your friends who could not be bothered to squeeze themselves into an essentialist stereotype were, of course, looking for convenience. Back to the beige board, the quiz will be on Tuesday.

Nikola Pejaković could not have said it better.

Moving onward to the second largest room in the exhibit, twice as large as the Kingdom room. Welcome to the fabulous world of repression! Because there were people, apparently, who could not even be bothered to be lazy and so they had to be forced to do some awful thing that remains unspecified. And so we get a catalog of people abused for their films, speeches, writings, and ideas. The problem here is that Yugoslavia was not all that repressive, so it is necessary to dig a bit to find visually appealing instances. Here the influence of one the exhibit’s authors, Srdjan Cvetković (best known to the public as the head of the Commission for Digging Up Random Stuff and Calling It Draža Mihailović), is visible. The room features a little table meant to be reminiscent of detective films from the 1950s, on which there is a lamp with a third-degree bulb and a little dossier listing prominent victims of Nasty Commie Repression (NCR). Do you want people who were killed? That’s a bit of a shame, because most of the really impressive cases in the dossier are from 1944. So all right, you’ve got your Goli Otok, you’ve got a handful of films and books that were banned, what else have you got? Why the heroes of free speech, of course: lovely folks like Franjo Tudjman, Vojislav Šešelj and Gojko Djogo. What a suffering state this Yugoslavia was, you think to yourself, as you leave the room silently bemoaning the sad, sad fate of Gojko fucking Djogo.

The Cvetković room was no fun, so let’s move on to the biggest and happiest room, the Hrvoje Klasić room. Yugoslavia was awesome! People came to hang out on the beaches! There’s Plitvice, it’s pretty! Haile Selassie spent all his weekends! They won a bunch of sports championships! Haile Selassie came by again, but this time with Sukarno, who looked gloomy and mean and had a smaller car, so let’s forget about that! Elizabeth Taylor came to hang out, folks, Elizabeth Taylor! With her husband, whatsisname! The players of Manchester United gave Tito a colourful footie ball!

Anyway, that was pleasant, back to the dominant ideologal frame of the exhibition.

Because let’s stop kidding ourselves, interethnic tension, a few sad people who got shot in 1944 and Elizabeth Taylor are just a sideshow to what we all know Yugoslavia was really about, and that is bad economic decisions. There’s a little corner called “failed investments,” and a little corner called “bad debt.” Now we’re talking.

The narrative runs into some difficulty here, though. Because, yes, like every state Yugoslavia made some bad economic decisions, and like every socialist state some of these bad decisions were made bad by ideology. And like every state, it also made some good ones. And in every case, what made them bad or good was their outcome, and this depended more on external factors and international contexts, things like the global availability of credit and the price of energy, than it did on what the decisionmakers believed they were doing. As long as we are at the level of basic economics, we might as well point out that most indicators do not point to an unbroken record of failure from 1945 to 1991. In fact Yugoslavia educated, employed and housed a large number of people, carrying them along a route of rapid (if not thorough) modernisation and except for those instances when economic cycles went way down, doing it at an improved standard most of the way. On the one hand there is no point in hiding the places where the system failed, but on the other hand there is no point in papering over a genuinely mixed record to fit a backward-looking stereotype of Communism.

This is probably where the central part of the story gets missed. It seems that the biggest absence of the exhibition is already apparent at the beginning, where identity is reduced in an essentialist way to the foregrounding of 19th-century empires and actually existing Yugoslavs are dismissed. If you want to deny the existence of Yugoslavs, you can do the job by looking at what surrounded them and not at what they were. So we get economics without economic actors, consumption without communication and desire, and a whole series of specific objects whose origin is vaguely identified as “druga polovina XX veka.” In sum what we get is a discussion of the state and its poor oppressed elite, with no reference to culture – to the lives of people in the state.

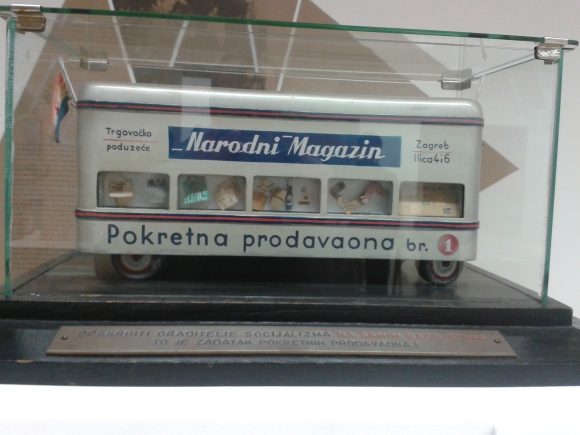

So from the beginning to end of Yugoslavia, what happens in the world of culture? Consumption mostly. Hey, there’s a Digitron! Look, here’s the little tram car that was used to encourage workers to buy things!

Culture is reduced in the presentation to consumption, which was often interesting but at least once the 1960s boom hit, never equaled the standard in more prosperous states. But what is missing from the account is that consumption is never just about the exchange of money of goods; it is also about the exchange of meanings and the development of communicative capacities. To the degree that Yugoslavia was something that people could identify with – identity that meant something in their lives and could not be reduced to a response on a census form – it was because the consumption that seems so rudimentarily charming operated within a meaningful context of culture.

I would say that the exhibit says nothing about culture, but that is not entirely accurate. It has a little section devoted to Neue Slowenische Kunst, an art group that engineered a well-publicised provocation in 1987 and has operated as a lucrative exercise in self-marketing ever since. NSK is kind of amusing, but you would have to be well Žižekked to reduce all of Yugoslav culture to them. Similarly the little corner on gender: there is loads to say about gender, especially in the context of rapid urbanization of a mostly pastoral society, but what this exhibit has to say is all about participation in the labour force. Apparently as a part of this there were women who carried agricultural implements, some of them large and pointy.

So a state that made bad decisions and meant nothing, how does it end? Meaninglessly of course, not with a bang but with a sculpture. That is what we are told in the last little room on the dissolution of the state and its descent into violent conflict. What we get in this room is a couple of video screens showing us old clips from dear old RTS and three abstract sculptures wrapped in black plastic. There were no political actors involved, no processes, no engineering of conflict, no crimes and no victims. If it were an incident from the Second World War the historians might have called it an information-like massacre of curiosity.

So there you have it. The nonaligned movement was a success. Everything else was a failure. Haile Selassie was stylish and Tito had some excellent spectacles. And like me, you are sorry you asked.

4 replies on “My only friend, the end”

while I agree that historians and especially museums in Serbia suck. Damn, I bring a bunch of American students to ex-YU every year and while we get a splendid show in Srebrenica and Croatian Jasenovac, we get NOTHING in RS Jasenovac and NOTHING in Belgrade to show about genocide against Serbs. I literally called “the Museum of genocide” in Belgrade (there is no internet site)…

– Hello, is that a Museum of genocide?

-Yes, how can I help you?

– Great! I have a student group from America here and we would like to visit the Museum, can you tell me the hours, you know, there is no internet site and it is better to check…

– Oh, really?

– Yes, you see, we came from Bosnia few days ago and students were very disturbed and impressed by the exhibition in Srebrenica, so it would be nice if they could learn something about genocide in NDH because…

– Yes, I see, but we have no permanent exhibition.

– Oh? Soooo… what do you have?

– We have a corridor. And our offices. Where we work, you know. Research.

– So, you have a corridor?

– Yes, I wanted to tell you, we have photos in the corridor…

– Photos?!

– Of chiildren. You know, from Jasenovac. Black and white.

– …

– We can also talk to your students, but we leave at 4pm, just so you know…

-…

– Hello?

– Thank you… Good bye…

*click*

I may have said “good bye” after I hung up. I was shocked. I still am.

Serbs have no intellectual capacity to tell their full story without apologizing to anyone, but with understanding of the Western standards of storytelling. They don’t even have the capacity to grasp the story for themselves, let alone to present it to you. And you expect them to have any understanding of malleability of identities? Of people genuinely identifying as Yugoslavs out of love, out of pride, pride that your father was born in Croatia and your mom in Serbia (guilty of that, until 1991) and not out of convenience?

They are even that stupid to allow non-Serbs to participate in this exhibition, instead of telling the story of Yugoslavia the way that suits their present interests. Before you accuse me of being evil: Do you see anything better done in Bosnia or Croatia? Jasenovac exhibition is a shameful play, and I don’t remember Serbs were invited to contribute. While Srebrenica exhibition proudly sports side by side photos of Auschwitz and Srebrenica. Quite good comparison? Professional? Yeah, right. That thing aside, I would try to tell a story as true as possible, regardless of Serbian interests. I just wanted to show how ignorant Serbs are in this respect.

In the end, it is quite amazing how easily you brush off things about Yugoslavia that you seem to dislike to hear. Yes, communist crimes were much bigger and gruesome than it is decent to mention. Yes, they were punishing free speech, even though Yugoslavia was more “liberal” than others. Yes, you forgot to notice whether the exhibition dealt with Cestna afera, Maspok, Kosovo issue at the hands of communists pre-Milosevic (exactly, 1968, 1981, if nothing else), to mention some highlights only. When it comes to economy, yes, I grew up with Cockta, Cokolino, Eva sardines and bunch of other products from other parts of Yugoslavia and yes, I was proud to feel Yugoslav, but during that time, Yugoslav market was super-fragmented, so much so that some goods were sold to foreign companies who would then resell the goods to other Yugoslav companies, without the goods ever leaving Yugoslavia. Thank you Zakon o udruzenom radu and 1974 Constitution! Thank you, withering away of the (only Yugoslav) state and thanks to defeat of “unitarism&statism” (but only Yugoslav, not Slovene, or Croatian, God no!). In the end,, we had Milan Kucan saying (paraphrasing) – Yugoslavia exists because of economic interests and not because of the past, kinship, shared values and ideas, etc. Thank you, Slovenia!

So what’s my point? Yes, the Museum of History of Yugoslavia sucks. I take students there every year, next summer being the 4th time. It sucks because it is a good space, Tito’s grave is there, location is not bad, yet Serbs don’t know how to use it for promoting their own understanding of Yugoslavia and how it damaged the Serbs, so the new generations would learn from past mistakes. Alas, how could they, they still have Croatian king Tomislav and Slovene prince Kocelj at the entrance of the Serbian parliament, sharing space on equal footing with Tsar Dusan and Karageorge, while Serbian parliament is covered with Yugoslav symbols. I’ve been few times in Croatian Sabor. I almost wished I was a Croat, what a splendid story has been told in the corridors and on the walls of that magnificent edifice!

Mladen, yeah, I know what you mean. On the other hand, if you don’t do the identity stuff, it’s hard to do much else. Eric

Hi Eric,

Happy New Year to you and yours!

I thought of you when I spotted this little Tito-nostalgia item (in the Daily Mail, of all places):

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/travel/article-2254176/Titos-train-Chance-explore-Yugoslavia-presidential-style.html

The themes — “Conference room: Tito is said to have entertained some 60 world leaders on his train!” — echo those of the Muzej istorije Jugoslavije exhibit. However in this case it’s all šobiznis, without much pretense that the ride will help anyone to understand the country’s history. One wonders how long those velvet-covered settees and Bokhara carpets, once reserved for the butts and boots of dictators, will hold up under the feet of the tourists.

Veliki pozdrav,

András

Let’s see if I can insert a photo into a comment. This is from the remarks by visitors board.

https://plus.google.com/u/0/photos/100943553508677170087/albums/5828926269892417297/5828926276643132578