You can read the Karadžić verdict too! It’s right here. It’s 2615 pages, so make yourself comfortable and set aside some time. If you haven’t got the time, here are a few questions and answers.

You can read the Karadžić verdict too! It’s right here. It’s 2615 pages, so make yourself comfortable and set aside some time. If you haven’t got the time, here are a few questions and answers.

There was no genocide before 1995, really?

The most discussed fact about the Karadžić case is that he was convicted at all. The second-most discussed fact is that he was acquitted on the first genocide count, for systematic killings in 1991 and 1992 in “the municipalities.” Some commentators are interpreting this acquittal as a denial of facts. This is untrue. The judges accepted the facts and described them in hundreds of pages of horrific detail. What they concluded is that the facts amount not to genocide, but to multiple crimes against humanity.

How did they do this? Let’s begin with the crimes against humanity. Karadžić was found guilty of six crimes against humanity in “the municipalities”: persecution, extermination, murder, deportation, forcible transfer, and “other inhumane acts” including rape and sexual violence. These crimes resulted from “intentional actions” (paragraph 2449) of the forces he controlled, and represented “a clear pattern of widespread intimidation, violence, killings, and expulsions targeted at the Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats“ (paragraph 2623). The crimes had major and lasting effects to the degree that “the scale and extent of the expulsions and movement of the civilians from the Municipalities, including the Count 1 Municipalities, resulted in the displacement of a vast number of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats and in drastic changes to the ethnic composition of towns with almost no Bosnian Muslim remaining there” (paragraph 2624). They were not incidental but, “Having regard to the clear systematic and organised pattern of crimes which were committed in each of the Municipalities by members of the Serb Forces, over a short time period, the Chamber finds that these crimes were not committed in a random manner, but were committed in a co-ordinated fashion” (paragraph 3445). Consequently, “the Chamber finds beyond reasonable doubt that between October 1991 and 30 November 1995 there existed a common plan to permanently remove Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Croats from Bosnian Serb claimed territory through the crimes” (paragraph 3447).

Sounds a lot like genocide, doesn’t it? Well, the judges gave two reasons for saying no. The first was that although some elements of crimes for genocide were demonstrated, including killing and causing serious bodily harm, one other was not. Despite affirming extensive evidence that showed levels of abuse, mistreatment, starvation, neglect and deliberate creation of high risk, the judges determined that the conditions in detention facilities did not reach the level that they could conclude that they were “calculated to bring about the physical destruction” of the group (paragraph 2587).

The second reason is probably the more important one. This involves the question of whether Karadžić had “specific intent” to commit genocide. Intent is the element that makes genocide most difficult to prove. For example, regarding the genocide in Srebrenica – on which there already exists a judicial record, and for which Karadžić was convicted in Count 2, the judges established his intent by following the timeline of events and his activities very closely, and determining that he only began to share the “specific intent” once the killing was already under way, based on a conversation with an operational commander that took place on 13 July 1995. Here is the text of the conversation:

- : I’m waiting for a call to President Karadžić. Is he there?

- B: Yes.

- : Hello! Just a minute, the duty officer will answer now, Mr. President.

- B: Hello! I have Deronjić on line.

- : Deronjić, speak up.

- D: Hello! Yes. I can hear you.

- : Deronjić, the President is asking how many thousands?

- D: About two for the time being.

- : Two, Mr. President. (heard in the background)

- D: But there’ll be more during the night.

- […]

- D: Can you hear me, President?

- : The President can’t hear you, Deronjić, this is the intermediary.

- D: I have about two thousand here now by […]

- : Deronjić, the President says: “All the goods must be placed inside the warehouses before twelve tomorrow.”

- D: Right.

- : Deronjić, not in the warehouses over there, but somewhere else.

- D: Understood.

- : Goodbye.1

Ham-fisted coding aside, what Karadžić is asking Deronjić to do in this exchange is to take civilian prisoners from Bratunac, where they were being held, to Zvornik, where they would be murdered. In the judges’ opinion this exchange marks the emergence of agreement between Karadžić and the military commanders that the theme had changed to “where — not whether — the detainees were to be killed” (paragraph 5805), and consequently the beginning of his personal engagement in the action to commit genocide.

The marked specificity of the conversation derives from the high standard for conviction. To find genocidal intent the judges did not ask “does it make sense?” but rather “is it the only reasonable inference that can be made?” This is an indication of how very high the threshold for a conviction on charges of genocide is.

So what did they find on intent on Count 1? Paragraphs 2596 and 2597 affirm the character of the nationalist ideology that sought to create an ethnically homogeneous state. But they determine that the inference remains open that this goal could be achieved by methods other than killing. Similarly with inflammatory statements and threats to “exterminate,” “annihilate” and so forth: in paragraph 2599 the verdict determines that these threats might be hyperbolic figures of speech and that the judges are “not convinced that the only reasonable inference to draw from these statements is that the respective speakers intended to physically destroy” the groups.

Probably the key passage explaining the judges’ decisions that the crimes in “the municipalities” did not constitute genocide is in paragraph 3466, “The Chamber is of the view that another reasonable inference available on the evidence is that while the Accused did not intend for these other crimes to be committed, he did not care enough to stop pursuing the common plan to forcibly remove the non-Serb population from the Municipalities. While the Chamber considers that these other crimes resulted from the campaign to forcibly remove the non-Serb population from the Municipalities, the Chamber does not find them to be an intended part of the common plan.”

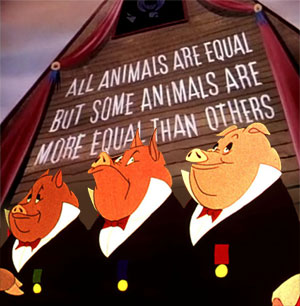

That was the argument in legal context. Outside of the legal context, what the judges found was yes, the goal of RS was to create an ethnically homogeneous state by forcibly changing the population, but they thought that they could do it without killing. The fact that they did killing does not mean that they thought they had to do killing. Take the argument for what it is worth. It is probably worth most as an example of the difference between legal reasoning and every other kind of reasoning. It is most likely also an indication that, at least at this early stage, judges are very reluctant to make findings of genocide.

Is the acquittal on Count 1 a victory for Karadžić?

To a degree, yes, in the sense that he was acquitted. But the factual findings are extensive and point to a large scale series of crimes, planned and coordinated at the highest political level.

There are two groups of people who are likely to be interested in the distinction between a finding of crimes against humanity and a finding of genocide: 1) lawyers, and 2) politically active people seeking to build political capital out of the presence or absence of the latter label. Their motivations and interests are not the same, are probably not commensurable with one another, and are generally not helpful to people outside of the communities that bicker about them.

Crimes against humanity are not minor crimes, and not necessarily lesser crimes than genocide. It is meaningful that on the basis of facts established at trial that Karadžić was convicted of major crimes, even if the conviction was not for every count that was sought. Beyond this, though, in the end what will matter most about the verdicts of the Tribunal (the well reasoned and documented ones, that is) will not be the decisions that are described in them. Those decisions are artefacts of what a particular set of judges were prepared to do at a particular moment in social and political history, at a particular stage of the development of their profession. What will matter about the verdicts will be the documentary record that they establish and their contribution to affirming the existence of facts.

Why did he not get a life sentence?

The sentence given to Karadžić is the product of the judges trying to balance the “gravity of crimes” for which he was convicted against the “mitigating circumstances” they are obligated to consider.

Nothing was considered as an aggravating circumstance. This may be because some of the potential aggravating circumstances in this case are attributable not to Karadžić but to someone called Dr Dabić. Factors interpreted as mitigating circumstances included Karadžić’s resignation from public office under political pressure in 1996 (the judges remained agnostic as to whether this was a consequence of the so-called “Holbrooke Agreement,” and the much-loved actor Hal Holbrook appears to have been unwilling to testify), and the fact that “in a few instances, the Accused expressed his regret” (paragraph 6059). His age was also taken as a mitigating circumstance.

ICTY sentencing is also bound by the sentencing practices that prevailed in Yugoslavia, which for these crimes were vague – the judges note that “Article 141 of the SFRY Criminal Code prohibited genocide, Article 142 prohibited war crimes against the civilian population, Article 143 prohibited war crimes against the wounded and sick, and Article 144 prohibited war crimes against prisoners of war. The offences under Articles 141, 142, 143 and 144 of the SFRY Criminal Code were punishable by imprisonment for not less than five years or by the death penalty” (paragraph 6042). So “something between five years and death” gives a lot of leeway, particularly in the absence of previous experience.

We might add here that a 40-year sentence (minus credit for 8 years time served makes 32 years, minus the “Meron bonus” of automatic release after serving two thirds of the sentence makes 19 years) does not necessarily mean less prison time than a “life sentence.” A life sentence does not actually mean that the prisoner will be held until death. This is because unless you are a soldier in one of the units commanded by Karadžić, you do not know when other people will die. So the life sentence is generally interpreted as carrying an arbitrary maximum determined by such factors as life expectancy and, in the case of ICTY, the notoriously lenient sentencing procedures of SFRJ. So these factors could in fact make a “life sentence” considerably shorter than the 19 years anticipated for Karadžić.

In that sense it could be said that the fact that Karadžić did not receive a life sentence has mostly symbolic meaning. This is compounded by the fact that the likelihood that he will live another 19 years is statistically low. But – to say that something has a symbolic meaning is not the same as to say that it has no meaning. In the first place, there is an obvious disjunction between the extreme gravity of the offences and the limited sentence. In the second place, symbolic issues are the issues on which people (everywhere, but particularly in the region) are least willing to give ground.

Will there be appeals?

Will there be appeals? Is my dog comical? Where there is a right to appeal there will be an appeal.

Should people be satisfied?

So is the Tribunal, pro-Serbian, anti-Serbian, moderate on Klingons, or what? It is none of those things, and any of the – many – people who are saying that the verdict is a verdict on some abstractly conceived ethnonational group simply do not know what they are talking about. Ignore them with the contempt they deserve.

And permit me an observation about claims of bias, particularly ones based on identity: they might have a little bit of value in terms of anticipating something that could happen in the future (“Mary is coming for dinner on Friday, and she is Catholic, so maybe she will want fish”) but they have no value at all in explaining facts that have already happened (“Mary overcooked the fish because she is Catholic”). This applies to whatever extraneous nonsense people might use to explain away the verdict (“the presiding judge is Korean, and they are jealous of Serbs because their pickled cabbage is more tender”), and also to deliberately unrepresentative nonsense people might invoke to flatten out the complexity of responses (“I talked to somebody who has been closely associated with this kind of extremist politics for years, and therefore I know what everyone from this person’s ethnonational group thinks”). To explain actual occurrences you need to engage with the actual substance.

As to the concrete question of whether people should be satisfied, who am I to tell people what should satisfy them? Some people will be pleased or displeased with verdicts on particular counts or with the length or shortness of the sentence. Some people will be delighted that the Tribunal has finally brought a genuinely major trial to conclusion. Some people will see convictions on 10 of 11 counts as a partial victory, some will see a symbolic loss on the genocide question as a crushing defeat. Most people, sadly, at least in the short term, will see this or any other event as confirmation of what they have believed all along.

What I might be able to suggest to people who are not certain whether to be satisfied is this: the measure of success or failure of this verdict will not be in where Radovan Karadžić makes his residence between now and his death, or in what a gaggle of self-seeking politicians will do in the next week or month. It will be in whether, over the long term, facts that have been established by a combination of investigation and argument enter into understanding and begin to provide a ground for discussion and mutual recognition among people who are aggressively taught by a phalanx of institutions that they need always to think of themselves as victims and of the people around them as their enemies. Whether this happens depends a lot less on anything the Tribunal does, and a lot more on the social and political environments in which people live.

Maybe it is worth adding another point: it is probably not a good idea to look for satisfaction in law.

What does this do for history and reconciliation?

Let’s start with history, because that is the easy part.

First, the verdict brings together documentary evidence regarding a very broad scale of crimes – although limited to Bosnia-Hercegovina, it effectively does what the verdict in the trial of Slobodan Milošević should have done if the trial had not outlasted the defendant. In the end this substantive degree of detail is going to matter a lot more than decisions on whether or not to convict or whether a crime is of one type or another. The really valuable job here was done not by the lawyers who sat on the bench but by the researchers who gathered material for their use.

The verdict continues the narrative that has developed at the Tribunal that the conflict in Bosnia-Hercegovina was a civil war, finding that despite the extensive evidence of coordination, political representation, arming, training, financing and repeated instances of direct of exercise of political influence, that neither Slobodan Milošević (paragraph 3460) nor his lieutenants Jovica Stanišić and Franko Simatović (paragraph 3461) were part of the joint criminal enterprise (their employees Šešelj and Arkan were, though, according to paragraph 3459).

As for reconciliation, we have seen two types of public statements. The first kind are platitudes from global politicians expressing a vague hope that the verdict will somehow contribute to reconciliation. These statements are worthless. The second kind are from politicians in the region who do nothing to promote reconciliation saying that the verdict will not promote reconciliation. These statements are less than worthless.

These sorts of statements indicate something that ought to be obvious: no verdict on any matter by any court is going to substitute for what a whole complex of institutions is failing to do about reconciliation. They could have begun in earnest before Karadžić was tried. They could still do it if the outcome of the trial were different. They could have done it if Karadžić were never tried. They can do it now.

You can read the Karadžić verdict too! It’s right

You can read the Karadžić verdict too! It’s right

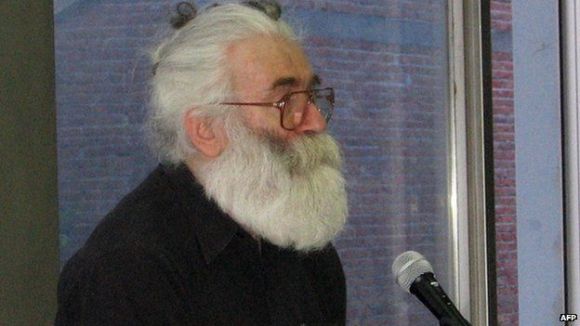

On Thursday the verdict will be delivered in one of ICTY’s last major cases, the one against Radovan Karadžić. You all know who he is and what he did, so no need to go into the details here: if you want to refresh your memory,

On Thursday the verdict will be delivered in one of ICTY’s last major cases, the one against Radovan Karadžić. You all know who he is and what he did, so no need to go into the details here: if you want to refresh your memory,

If you read this blog, then you already know about the interesting post-election political developments in Croatia. Following on a result that saw the two largest parties more or less tied, with a surprisingly large vote going to a protest party composed of dilettantes and small-scale egomaniacs, a presidential attempt to stage a coup and impose a “non-party” government under her control was avoided, and the protest party eventually decided, after several feints left and right, to form a coalition with the right-wing

If you read this blog, then you already know about the interesting post-election political developments in Croatia. Following on a result that saw the two largest parties more or less tied, with a surprisingly large vote going to a protest party composed of dilettantes and small-scale egomaniacs, a presidential attempt to stage a coup and impose a “non-party” government under her control was avoided, and the protest party eventually decided, after several feints left and right, to form a coalition with the right-wing